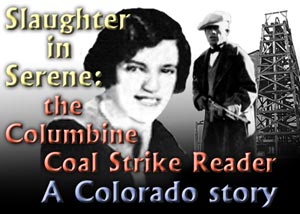

Slaughter in Serene: the Columbine Coal Strike Reader

Available now!

Rocky Mountain News book review

Book information follows article...

Slaughter in Serene

Grim-faced Walsenburg strikers in front of IWW hall where two Wobblies were killed by state police an hour earlier, January 12, 1928. Detail from photo below. Photo courtesy Wayne State University, provided by Eric Margolis

The 1927 Strike

by Richard Myers

In 1927 the Industrial Workers of the World called a general strike to protest the execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Compliance with the walkout on the part of Colorado's coal miners surpassed all expectations.

This occurred in the state that had given us the Western Federation of Miners, Big Bill Haywood, Cripple Creek, and the 1914 Ludlow Massacre in which the lives of women and children were sacrificed to corporate greed. Colorado had seen discontent and uprisings by coal miners over a period of some fifty years. For many, Ludlow seemed a watershed, an event that drew worldwide attention to the state's policies of industrial feudalism. Ludlow ushered in Rockefeller's company union and the birth of the public relations industry to repair John D.'s reputation. But Colorado's coal operators were not yet finished spilling the blood of workers.

Conditions in the mines were desperate. Miners complained that coal bosses didn't give a damn about their lives. They observed that mules used to haul the coal were treated better than the men. It cost money to purchase and train mules; men could be hired for nothing, and then forced to pay their own expenses.

Miners were not paid for "dead work" such as timbering that kept the mines safe. They had to pay for their own tools and blasting powder. Miners were cheated at the scale that weighed their coal. Many coal companies paid in scrip redeemable only at the company store. Coal towns were armed camps surrounded by barbed wire. Perhaps most frustrating, Colorado coal miners had suffered significant pay cuts in recent years.

Slaughter in Serene: the Columbine Coal Strike Reader

Book signing with authors and editors.

The Thursday, January 12 book signing at the Lafayette Public Library, the third in a series, drew 130 people— miners, their families, historians, students, and folks interested in the history. Thanks to all who made it a wonderful evening.

With little consideration given to safety, Colorado coal miners had been dying by the hundreds. A decade before the Columbine Mine Massacre, 121 miners died in an explosion in the Hastings mine. In 1919, 31 were killed by explosions in the Oakdale and Empire mines. 1922 and 1923 saw 27 killed at Sopris and Southwestern. These were only the big events; miners were dying individually almost every day.

Colorado miners honored the Sacco-Vanzetti general strike because they were unhappy about conditions on the job. Recognizing their discontent, the Wobblies organized a coal strike. Striking miners shut down every one of the 14 coal mines in northern Colorado except for the mighty Columbine, situated north of Denver in the small company town of Serene. The Columbine normally employed 500, and they successfully lured 150 scabs to work during the strike by granting a fifty cent per day raise.

Throughout the state 12 mines were still operating on November 1, the fifteenth day of the strike, while 113 mines had been closed. The Denver Morning Post reported that 1,750 miners were working, while 8,450 laid down their tools. Newspapers frequently portrayed the strike as faltering, dutifully parroting the company line that "many miners are expected to return to work on Monday." But strikers systematically demonstrated that mass rallies in the Southern Field could bring out the miners. Week after week the Denver Morning Post repeated the phrase, "The backbone of the strike appears to be broken," even within the same column that detailed additional mines closing down. Caravans of strikers brought food, donated material goods, and car loads of enthusiasm to support local union efforts. Many miners simply had to see with their own eyes that the strike was succeeding.

Colorado had an anti-picketing law which prohibited any sort of speech with persuasive intent relating to hindering commerce. Strikers suffered many arrests simply for picketing, and police locked up anyone they could identify as an organizer. In Huerfano and Las Animas counties some IWW activists were arrested on vagrancy charges as soon as they appeared in public. In Walsenburg "agitation of strikers"—speaking to miners on strike—was considered a crime.

Because the Columbine was a large mine that continued to work, it was a focal point for the strike effort. It likewise became ground zero for a plan by coal company operators and the state of Colorado to break the strike. The mine was owned by Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, a corporation in the midst of change. Josephine Roche, daughter of the recently deceased owner, insisted that rights of the strikers be respected, but she was not yet in full control of the company. Officials of other coal companies maneuvered behind the scenes to orchestrate a bloody confrontation that would bring Colorado's notorious National Guard into the field.

Colorado militia searching cars during the Wobbly strike. Photo credit Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, provided by Eric Margolis

Roche held liberal views which had led her to a career in social work and a stint as Denver's first police woman. She patrolled Denver's bustling "entertainment district" where prostitutes plied their trade. She was no stranger to the strife of coal miners and their families, having participated in an investigation of Ludlow, and she ultimately went to work for the United Mine Workers union after Rocky Mountain Fuel Company failed.

Women powerfully influenced the struggle on both sides of the picket line. In the Columbine Coal Strike Reader Eric Margolis writes,

As was typically the case in mine strikes, the wives played an important role. [Coal miner] Louis Bruger laughed and said: "They didn't know any more about mining coal than the hog knew about Sunday, but they'd be right up there giving the men hell for not fighting harder..."

On November 8 the Denver Morning Post headlined, "WOMEN MARCHING AS PICKETS TURN BACK BEFORE GUNS". They didn't always turn back; when bullets flew, some of the most seriously injured were women.

Headlines of another Post story declared, "Strike Control Passes Into Hands of Women—Hordes of Amazons Storm Jail Demanding to See Deported Sons and Husbands; Mexican Mother Assumes Leadership With Fiery Speech." The article continued,

Leadership of the I.W.W. strike at Walsenburg today passed into the hands of the women with an Indian halfbreed, Mrs. Felix Arrellano, at their head.

"If we were asking for diamonds we wouldn't deserve them," she began her morning address. "But we are asking for bread..."

And the women are behind her. Their enthusiasm, slow to catch fire at the start of the strike, was fanned to a brisk flame by this wobblie Joan of Arc.

Historian Joanna Sampson chronicles triumphs and travails of women on the picket line, including Colorado's own rebel girl, Flaming Milka:

The fistfight was bad enough, but when the women in the strike line entered into the spirit of the ruckus, it was humiliating for the police.

Amelia (Milka) Sablich was the IWW "girl in flaming red." She and Sadie Romero were in fine fighting form that day. With fists flying and screaming curses at the police, they both plowed into the fray.

"Flaming" Milka was no stranger to the picket lines. She had already been arrested several times and hospitalized once after a fight.

On October 28, Milka Sablich led 250 strikers on a march at the CF&I Ideal Mine in Huerfano County. That morning twelve gunmen met them with drawn bayonets, and there were another twenty-five guards mounted on horseback. Accounts of the incident are contradictory. The guards swore that an unruly horse knocked Milka down, breaking her wrist and inflicting possible internal injuries. The miners, however, reported that one mounted guard leaned out of his saddle, seized the fiery young woman, and galloped down the road, dragging her behind his horse.

When authorities arrived at the hospital with the injured girl, her red dress torn and dirty, her body covered with bruises (and slated for jail as soon as she was patched up) they discovered that she was 19 years old, beautiful and, like a caged wild cat, spitting hatred at her tormenters.

Newspaper reporters immediately drew comparisons between Milka and famous Mother Jones (who looked like a prayer meeting leader, but could hold her own with any army muleskinner). They decided Milka packed a meaner wallop.

Flaming Milka, Colorado's IWW rebel girl preferred jail over capitulation. Photo credit Industrial Solidarity, provided by Joanna Sampson

When Milka was offered liberty in return for a promise to stay away from strikers' meetings she flatly refused, preferring jail to walking away from her sisters and brothers.

Activities in the south—where John D. Rockefeller's Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) was located—included police padlocking union halls, fist fights, picket line altercations, and intimidation. Arrested IWW organizers were moved from jail to jail in a shell game to prevent access by IWW lawyers. Many IWW supporters were taken to the state line or left gazing at Colorado's snow covered peaks on an isolated stretch of prairie—a practice known as "white capping" since the Cripple Creek "reign of terror" days—and warned never to return.

But imprisoned Wobs didn't give up the fight. Seventy-five IWW members locked up in the Trinidad jail held a jailhouse demonstration which featured bonfires. In the north a strike committee was formed by Lafayette prisoners. When they were offered freedom they surprised their jailers by refusing to leave. They anticipated that if they vacated the premises the marshal would lock up other strikers, and since they had become acclimated to the jail they might as well stay to prevent such an occurrence. It took a week, and finally a suggestion that he was through locking up strikers, for the Lafayette marshal to convince them to vacate the jail. Another group of Wob prisoners in the town of Erie persuaded their jailers, much to the chagrin of their boss, Marshal Will Lawley, that if they formed a deputies' union they would obtain better working conditions and higher pay.

In Colorado the plight of the miners had long been ignored, and newspapers focused on the impact of the strike rather than the working conditions of the strikers. Winter was coming and coal stocks were dwindling. "Coal is available in small quantities, but prices are high, due to the fact that most of it has been shipped in from outside the state," lamented the Denver Morning Post. No one had expected the Wobblies to successfully shut down Colorado coal.

Not content to report the news, leading publications such as the Boulder Daily Camera and the Post blatantly demanded state violence to discipline the Wobblies. The Post declared that it was time for the state to unleash the "mailed fist", to "strike hard and strike swiftly..."

The Post faulted the IWW even when a demand from the governor to cease picketing had been followed:

I.W.W. pickets were ostensibly withdrawn from the southern Colorado mines, but actually they were merely transferred from the mines to the miners’ homes. The wobblies have substituted war on women and children for browbeating and bullying men...

But if I.W.W. pickets again appear at the mines today, there is nothing to do but invoke the full might of the state’s authority to answer their sneering defiance. The law and good order of Colorado will be upheld, and the I.W.W. will learn that a patient man, like Governor Adams, when aroused, strikes hard and strikes swiftly.

With considerably less inflammatory rhetoric the Rocky Mountain News characterized the visiting of miners' homes as "canvassing in the interest of the strike." But cheered on by apoplectic editorials in the Post, police arrested strikers for this covert "picketing." The News noted bluntly that two of the men arrested for this practice "are Negroes."

Prejudice against minorities or foreign born workers played a significant role in public attitude toward the strike. There was mock dive-bombing of union rallies by National Guard aircraft in the weeks before the massacre, and the pilots who engaged in the harassment expressed views in the Post that seem typical:

"We hope we are not called upon to reap destruction," the officers said, "but unless the strikers use a little common sense we may be ordered into action.

"We are not opposed to union labor but we are opposed to the wobblies. They are displaying the American flag prominently, but that means nothing unless there are American citizens behind the flag.

"The only safe place for them if martial law is declared is to dig a tunnel under the Spanish peaks where we can’t get them."

E. H. Weitzel, Vice President and General Manager of CF&I, vilified the IWW at every opportunity. "If you look up the records of your leaders," Weitzel told a group of strikers, "you will find that every one of them with the possible exception of one or two have criminal records and are undesirable citizens..."

The Morning Post promoted the idea that the miners had no right to strike because they were foreign-born. On November 7 they referred to strikers as "Mexicans, Italians, Bulgarians, Slavs, Negroes, Austrians, Americans, and nondescripts whose nationality was not apparent... Speeches were made in every language except pure English." The Post criticized their spelling, their speech, their dress, their personal hygiene, their values, and even mocked one organizer's lack of skill with a typewriter. IWW leaders were called "tramps with their pants pressed." Three days before the massacre the Post quoted unnamed officials warning that a thousand of "the foreign element will enter the state" as a result of an appeal for footloose rebels published in Industrial Solidarity.

Meanwhile the company union at CF&I brought to the table two issues: a request for a dollar a day higher pay, and a resolution passed unanimously by the "employees' representatives" that the company fire any IWW members currently employed. CF&I granted a $.68 per day wage increase and agreed to fire Wobs discovered on the payroll. The company trumpeted these agreements as proof that the post-Ludlow company union was preferable to a strike by a "criminal" organization like the IWW.

Class collaboration is a conspiracy in which workers sacrifice their integrity for short term gain. Absent the ongoing coal strike, any pay increase at CF&I would have been laughed off the table by the haughty architects of the Ludlow victory. After all, they had just recently cut wages. Condemnation of the Wobblies by the company union provided CF&I with political cover for attacks on yet another group of workers. The straw bosses in Rockefeller's company union cynically swapped the last remnants of their honor for a pay raise. The emptiness of the charade became more apparent in 1931; with the Wobbly threat finally past, the wage increase was rescinded.

Ironically the miners found picket duty more forthright and pleasant at the Columbine Mine in the north. There had been confrontations and arrests, but there were also good memories. Historian Sampson reports an eyewitness account of the picket line from George Ychelich, a boarding house operator in Erie:

I went over there about every morning to see the fun: the women went along and they sang; the music was beautiful; the girls clapped their hands and sang their songs.

Years later the children of the strikers vividly recalled mugs of hot coffee and huge stacks of doughnuts which many believed were provided to the strikers at the direction of Josephine Roche.

IWW Band, Lafayette, Colorado

On Wednesday the Denver Morning Post reported that a machinegun had been taken to the Columbine. The paper added, "A number of additional deputies and state officers are expected to re-enforce the peace squad which has been on duty at the Columbine."

Thursday's Boulder Daily Camera ominously blared the arrival of the big gun:

"MACHINE GUNS ARE THE BEST ANSWER TO THE PICKETERS. POSTED AT THE COLUMBINE MINE, WILLING WORKERS GO TO WORK WHILE PICKETERS SLINK BACK. MACHINE GUNS MANNED BY WILLING SHOOTERS ARE WANTED AT OTHER COLORADO MINES..."

Early the following Monday the strikers arrived, expecting another peaceful rally.

Five hundred miners and their families were met at the outer gate by Weld County Deputy Sheriffs Louis Beynon of Frederick and William Wyatt of Greeley. Beynon warned the strikers not to enter the Columbine property. The strikers argued that Serene had a public post office—and some of their children attended the Columbine school—so they had a right to continue holding strike rallies there.

Beyond the gate the miners were surprised to see a new group of men dressed in civilian clothes but heavily armed. Head of the state police Louis Scherf shouted to the strikers, "Who are your leaders?" "We're all leaders!" came the reply. Scherf announced the strikers would not be allowed into the town, and for a few moments they hesitated outside the fence. There was discussion, with many of the strikers asserting their right to proceed. One of the police taunted, "If you want to come in here, come ahead, but we'll carry you out." Longtime Lafayette resident Lewis Starkey, then a miner from Erie, recalled later that he thought it was a bluff.

There was a sudden scuffle, with the police beating popular strike organizer Adam Bell about the head. Gravely injured, Bell collapsed to the ground, and the miners surged through the gate to protect him. The police retreated, then opened up with deadly fire directly into the crowd. In the early dawn light the miners scattered under a hail of lead. Twelve remained on the ground, some writhing in agony while others lay still. At least six died; more than sixty were injured.

Thirteen wounded strikers were taken to this doctor's office; crowds of concerned coal miners gather outside. Photo credit UPI, provided by Eric Margolis

Significantly, no police or mine guards were shot; the standing order in the IWW was to leave all weapons at home or at the union hall, so the miners carried no guns.

In a 1944 memorandum Miss Roche identified CF&I's Jesse Welborn as primarily responsible for the circumstances leading to the massacre. The company had closed mines and laid off 3,000 steel workers due to the strike. But the violence did not end with this massacre. More striking miners were killed by the state police in Walsenburg a few weeks later. Union halls were ransacked and shot up, their contents destroyed, their windows smashed.

The slaughter of miners at the Columbine Mine marked the last significant industrial action of the period conducted by the IWW, but it also became the catalyst for change in Colorado's coal mines. Rocky Mountain Fuel Company shocked the other coal operators by announcing that the strike had been caused by conditions. After gaining control of the company in the aftermath of the massacre, Josephine Roche declared that it was time to recognize a union—any union, that is, except for the Industrial Workers of the World.

Although miners had been brutally murdered at the Columbine Mine, the IWW successfully averted any violent reaction. Union organizers counseled angry miners with Joe Hill's words: "Don't mourn, organize." But preventing a violent response to the massacre apparently didn't endear the IWW to union-friendly Josephine.

As happened so frequently in the first half of the twentieth century, the workers were not allowed a free choice. Indeed, they were not even consulted. Roche declared that the union at Rocky Mountain Fuel Company must be affiliated with the American Federation of Labor. She ultimately invited the United Mine Workers to return to Colorado.

The United Mine Workers happened to be the very union whose members just five years earlier had engaged in the largest civil insurrection since the Civil War. That action in West Virginia came to be called the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Just over a decade earlier members of the UMWA had launched Colorado's own Ten Days War, blowing up mine camps and killing mine guards as a response to the Ludlow Massacre. (And after their wives and babies were murdered, who could blame them for their anger?)

I do not seek to criticize the UMWA for their members' collective response to violence. It just seems ironic that the AFL-affiliated UMWA, with ten thousand miners armed with thousands of rifles, liberal use of dynamite, and even their own machine gun, having engaged in outright war during two previous coal strikes, ultimately proved less threatening to Rocky Mountain Fuel Company than the non-violent wobblies, who believed and preached the radical notion that labor is entitled to all it creates.

ABOUT THE BOOK

There is a lot of fascinating information in the book that cannot be found on any website.

Slaughter in Serene: the Columbine Coal Strike Reader features the writings of Eric Margolis, Joanna Sampson, Phil Goodstein, and Richard Myers. Much of this material has never before been published. The book is available now. Availability from the Industrial Workers of the World is anticipated, price $19.05 plus shipping and tax if applicable. For information contact IWW General Headquarters, or the Bread and Roses Workers' Cultural Center, c/o P&L Printing, 2298 Clay St., Denver 80211, or call 303-433-1852, or email breadandroses@msn.com

Order: http://workersbreadandroses.org/

For more on the Columbine Mine Massacre, see the Columbine Story

Also see coal mining in Colorado

Click on image for enlargement, use scrollbars

Walsenburg strikers in front of the IWW hall where two Wobblies were killed by state police an hour earlier, January 12, 1928. Photo courtesy Wayne State University, provided by Eric Margolis

Protect the safety of coal miners, join Sago Outrage

Link to this page (link graphics):